The concept of affordance has first been explored by perceptual psychology and was originally only applied to physical objects. There are a few different definitions of affordance such as “[if] an object’s sensory characteristics intuitively imply its functionality and use” or “an object’s properties that show users the possible actions they can take with an object”. These definitions are mostly very similar and can be summed up as: an object possesses affordance if it gives you clues about how it should be used and therefore suggests ways of interaction.

Designing Affordance with the User in Mind

Regardless of whether a product is physical or digital: affordance can’t exist without design. Objects should always be able to do the things they are designed to do and also look like they are able to do those things. When designing objects, the question is at what point a design element stops being purely decorative and starts adding real value.

A handle clearly affords being gripped

However affordance doesn’t solely rely on the design, look and feel of an object. According to Don Norman, an object only affords the actions a potential user considers possible in the moment of use. Whether users expect an object to be able to do something also depends on the context of use, the user and their capabilities, intentions and past experiences with similar objects.

Since affordance is the ability of any given object to explain itself or make the way it should be used obvious, elements only possess high levels of affordance if a real user instantly knows how they can be used and what results can be expected in a realistic usage setting. For example when designing digital affordance you should consider the context of use as well as the degree of common sense and experience with using digital products you can expect from your users. Don’t explain things that are obvious but also don’t presuppose high levels of competency in the usage of digital products.

The different kinds of affordance

Physical objects usually rely heavily on their shape or other haptic characteristics to convey how they are to be used. Digital spaces have a harder times providing users with physical clues as to what can be done within them. Still there are a number of different ways to provide products with affordance:- Explicit: explicit affordance is provided by language and/or physical cues. The verbal guidelines provided are usually very clear. However you should keep in mind that an interface should be usable without verbally explaining every single step the user needs to take.

- Labels: labels are a form of explicit affordance and directly describe or state how the user is supposed to interact with a given interface. They should be used for complex interfaces and forms or for simpler interfaces that are designed for beginners. Descriptions or labels that use words are often supplemented with icons or symbols to make their functionality more understandable.

- Metaphorical: metaphorical affordance is related to skeuomorphism (parts of a digital object’s design imitate real-life objects). If you are uncertain of how to convey a certain functionality, it can be a good idea to think about real-life counterparts. E.g. users expect that the image of an envelope is somehow connected to sending emails. When using metaphors, make sure your users understand your metaphor or know its underlying meaning. Otherwise you will confuse and alienate users who are unfamiliar with that metaphor.

- Patterns: patterns are labels, icons, metaphors or other ways of interaction that are used by multiple designers around the web and therefore set out by convention. They are based on the power of users’ habits. One example of a pattern is the fact that most users expect that clicking on the Logo on a company’s website in the top left corner will lead them back to the main page. This doesn’t really make sense considering the way the logo looks or its context but still has been established across the internet. While it’s good to meet your users’ expectations by using common patterns, it can also have negative effects: for example it can be very hard to establish new patterns even if you figured out a better or more effective way of interaction.

- Hidden: hidden affordance is not apparent/visible unless a certain previous action has been taken by the user. One example for hidden affordance is a menu that drops down upon hovering over a certain part of the screen. It’s often used to simplify visual complexity, however users have to find the possible ways of interaction on their own which means they need a certain understanding of the interface in order for the hidden affordance to work.

- False: false affordance has the user believe that a certain action will lead to a certain result. However upon completing the action, either nothing or something unexpected happens. This usually happens by mistake (e.g. a broken link) or when design conventions are used in the wrong way (e.g. wrong usage of certain colors, underlined text that was never supposed to be a link, confusing placement of elements…). This should of course be avoided as it may confuse and annoy your users.

- Negative: negative affordance explicitly tries to show that an option might be taken under certain circumstances but is not possible right at that moment. An example for this would be a submit button below a form that is in an inactive state and can’t be clicked unless all required fields are filled.

Affordance in UX and UI

Why is affordance important for UX and UI design and increased usability of digital products? User cannot carry out the desired actions if the object doesn’t afford them. If there’s no clue as to how to use an interface correctly, users have to employ trial and error as their only strategy.

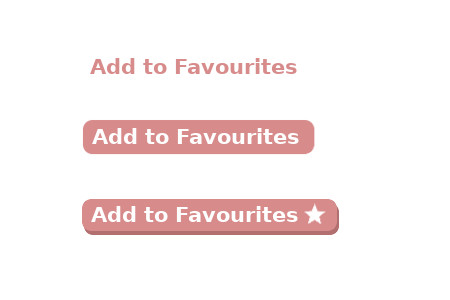

The increase in usability from top to bottom can be lead back to differences in affordance

When designing you should make sure people also notice your intended affordances because intended actions won’t be carried out unless the user perceives them as possible. Digital elements with an obvious affordance include buttons, fields, icons and menus. Try to avoid false affordances as users will be confused and wonder whether their interface is broken or they made a mistake.

As is the case most of the time when designing for users remember: you are not the user. Affordance only works when the user perceives an action possible. Don’t simply assume an affordance exists. If you are unsure tests whether it works using real users.

You’re interested in other topics related to UX/Usability/UserResearch? Have a look at our blog or hit us up on twitter!

in Germany

in Germany

Comments are closed.